Are SA bonds still attractive after the recent rally?

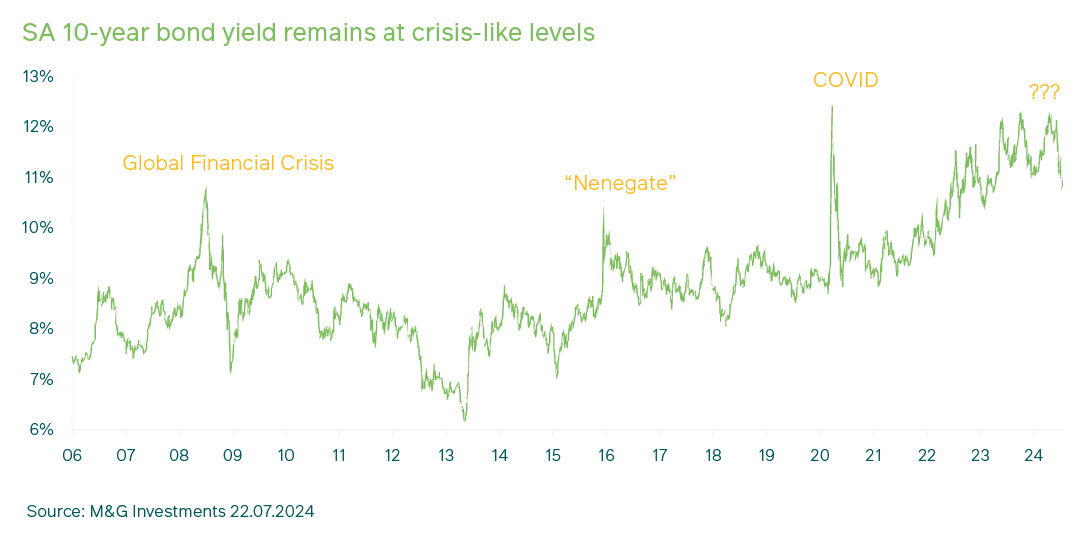

As an investor one is always in search of assets that are both priced attractively but also have positive fundamentals underpinning them. These are hard to find! Typically, you have to either compromise on the price or on how good the “story” is. South African government bonds provide an interesting example of this investment dilemma. Prior to the recent elections, the fundamental backdrop was very concerning, with investors having to contend with fiscal weakness, a poor growth outlook, and a highly uncertain election outcome. At that point, however, this backdrop at least came with a very attractive valuation, with the 10-year bond yield exceeding 12%, which was higher than where it reached during both “Nenegate” and the Global Financial Crisis.

Today investors find themselves in a significantly more positive political environment than most expected. The Government of National Unity (GNU) arguably brings with it better governance and oversight, continuity around financial policy, and a continuation of the much-needed structural reforms that were introduced under Operation Vulindlela. However, this greater policy and political certainty has come at the expense of a deterioration in valuation, with the 10-year bond yield now roughly 120bps lower than its pre-election level.

The question that investors should now be asking themselves is the following: “Have SA bonds become a more attractive investment prospect due to the political outcome, or is this asset now less attractive than before, given the more demanding valuation?”. Here we provide a brief overview of how we are thinking about this issue, with discussions around both the valuation as well as the fundamentals of the asset class.

1) Valuations are arguably still at crisis levels

Valuation relative to history

Graph 1

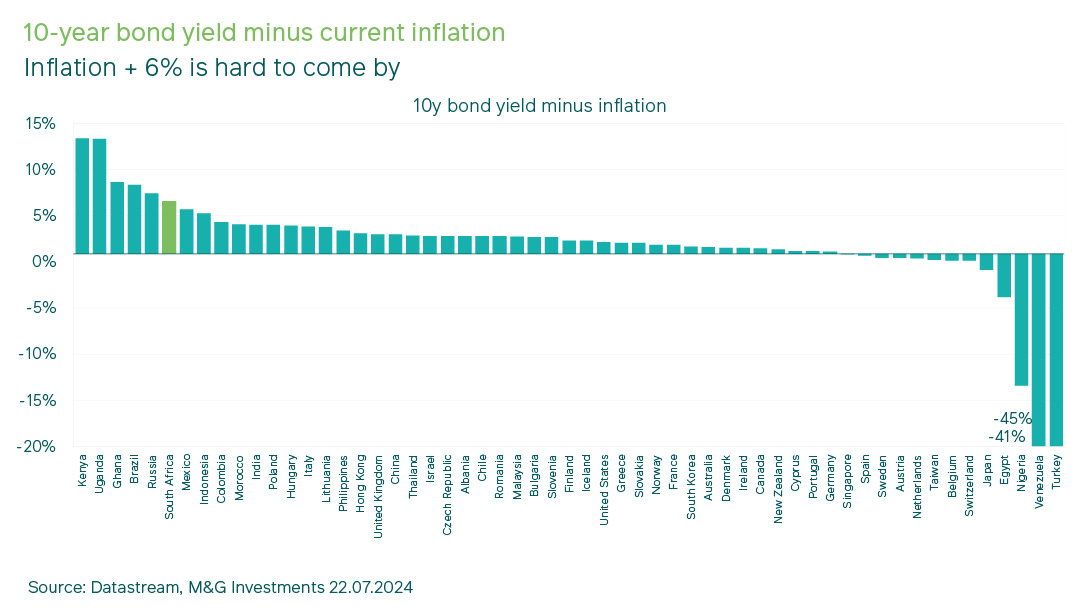

Looking at Graph 1, it shows how the yield on the SA government 10-year fixed-rate bond is currently very elevated compared to its own history at around 10.9%. Although the 10-year has rallied significantly since the election, its yield remains at levels that were only historically seen during crisis periods. Assuming inflation averaging 5% over the longer-term, investors could earn a real return of around 6% p.a. if held to maturity. This is more than double the roughly 3% p.a. long-term real return this asset class could be expected to deliver based on its history. It is also not far off the long-term real return that we expect from SA equities of 7% p.a. but comes with lower risk. SA bond investors are therefore still being compensated as if they are taking on equity-like risk. As the accompanying chart shows, there aren’t very many countries with real bond yields of this magnitude.

Graph 2

Equally, history suggests that the SA bond market typically delivered a return of around 13% p.a. over the next three years from a starting valuation such as this. Even though it is possible for things to turn out very differently this time, judging by history alone, the valuation remains compelling.

Government bonds versus credit and cash

What about other fixed interest investment opportunities? We think that fixed rate corporate bonds (credit) look expensive by comparison. Senior bank bonds, for example, currently trade at lower yields than government equivalents (despite coming with greater credit and liquidity risk). While it is possible to find weaker quality credit that is yield-enhancing relative to government paper, we think the overall starting point for credit spreads is too low (as illustrated by the banks), and as a result these riskier names don’t offer enough compensation for the risk that they come with.

We also view cash as a less attractive asset class. Our modelling suggests that, in order for cash to outperform bonds over the medium to long term, the repo rate would need to rise to 14.0% (from its current level of 8.25%) and would have to remain there for the foreseeable future. This is highly unlikely, in our view. Indeed, the repo rate has never exceeded 13.5% since inflation targeting was introduced in South Africa in 2000, let alone remained at these sorts of levels for decades on end. Moreover, the economic consensus suggests that we are at the peak of the repo cycle, and that the rate should in fact start to decline soon.

Local bonds versus global bonds

Finally, when we compare South Africa’s bonds cross-sectionally to a range of other emerging and developed market alternatives, they appear attractive on a number of measures. As illustrated in graph 2, very few countries’ bonds offer comparable real yields.

2) South Africa’s fundamentals are improving but remain challenged

Global monetary policy turning into a tailwind

Most developed markets have, in the last two years, gone through the most aggressive tightening cycle in three decades. Looking forward, economists largely expect global interest rates to start falling soon; indeed, some countries have already commenced with their cutting cycle (Canada, ECB, etc.). This means that global monetary policy is expected to shift from a considerable headwind to SA growth into a tailwind. Lower interest rates could perhaps also improve sentiment toward emerging markets and reduce global risk premia.

Supply-side constraints

With South Africa recently celebrating 100 consecutive days without loadshedding, the worst of the energy challenges are arguably behind us. Having said this, some challenges remain, especially around grid capacity, and we expect energy uncertainty to continue to constrain growth for some time. Meanwhile, the problems we are seeing at Transnet, such as costly breakdowns in national transport, ports and logistics networks, are acting as an additional brake on economic expansion and are also fueling inflation. These issues, being structural in nature, will take time to fix, regardless of how capable the minister is in whose portfolio these problems happen to end up.

Crime

The persistence of a high crime rate is another root cause for South Africa’s lack of growth that, unfortunately, has not been sufficiently prioritised by the government or Operation Vulindlela, in our view. The World Bank[1] estimates that crime costs the country a total of 9.6% of GDP every year. Crime is a partial cause of the structural issues at Eskom and in the transport and logistics sectors (including Transnet) through the existence of crime syndicates, but there have been few prosecutions. All three of these issues (i.e. energy, logistics and crime) can be seen as binding constraints on growth, or bottleneck issues, since it is extremely difficult to achieve a higher growth rate without each of them being significantly improved.

State of the fiscus

A very important fundamental factor that must be considered is South Africa’s fiscal health. In the past 10 years, South Africa has suffered a sharp deterioration in its debt levels as a percentage of GDP, from 40% in 2014 to 74% at the end of 2023. Few countries have experienced a comparable degree of fiscal slippage over this period. The biggest driver of this fiscal weakening, in our opinion, has been SA’s underwhelming economic growth. In order to stabilize the country’s finances and put us on a more sustainable footing, the economy would have to grow by about 8% per year in nominal terms, a growth rate not seen for most of the last decade.

Currently, the government is spending R19 of every R100 it collects on debt servicing costs, which places SA in the weakest 10% of countries globally, and the IMF projects that this will rise to around R25 of every R100 by 2028. This significant debt burden limits the degree to which government can undertake capital expenditure, and this lack of investment in turn negatively impacts economic growth. The latter typically results in weaker fiscal performance, which in turn can lead to more borrowing. In this manner, a poor fiscal starting point, along with weak growth, can result in this type of vicious cycle which is difficult for countries to recover from.

Some brief thoughts on the election

As already mentioned, the election outcome is a very positive development for South Africa. The way in which the ANC was willing to peacefully surrender power after governing for 30 years should not be taken for granted in a new democracy like SA’s. While we are optimistic about the policy continuity, diversity of viewpoints, and commitment to structural reforms that the GNU should bring, there are also a few reasons to be cautious.

Firstly, some of the ANC government’s policies arguably played a role in some of the key problems that we discussed above, such as the supply side constraints and poor fiscal health of the country. While the ANC’s share of the national vote has declined materially, the party does still occupy 22 out of the 34 positions in the new cabinet. It is worth asking the question whether the balance of power has shifted enough to result in the broader and more significant reform that many investors hope for.

Secondly, there are large ideological differences between the parties within the GNU, and it remains to be seen how they will cooperate on tricky political issues such as NHI, BEE, and Eskom’s municipal debt situation. SA is still relatively new to coalition politics, so how this will play out is unclear at this stage.

Lastly, the performance of the civil service will not solely be a function of the quality of the cabinet, but also depends crucially on the civil servants themselves. A highly capable minister may not be able to make the expected progress without experienced and capable directors general and other staff who function alongside them. With many skilled and experienced civil servants having retired in the past decade or so, the turnaround of certain government departments may take longer than investors would hope.

Balancing valuations and fundamentals

South African bonds clearly don’t fit the mold of an ideal investment case, which has both an attractive valuation as well as great fundamentals. The fundamentals are undoubtedly challenged. It is encouraging to see improvement in some of these issues, such as electricity, but others, such as crime and logistics, have a long way to go. Having said that, we think that at current yields, bonds more than price in all of this uncertainty. Fundamentals are problematic, but perhaps not quite as bad as the crisis-like levels implied by the market. While we have reduced our exposure to bonds somewhat, on the back of the post-election rally, we maintain an overweight position in SA bonds across our house-view multi-asset portfolios.

Clients who share our view that bonds are attractive can take advantage of these valuations via the M&G Bond Fund. Our recent article explains the investment process of the Fund, which has outperformed both its All Bond Index benchmark as well as its ASISA peers (ranking 3rd out of 40 funds in its category according to Morningstar), over the past three years. We hope to be able to extend this performance, and in so doing, provide investors with an additional return over and above the attractive returns we expect from the asset class.

[1] “Safety first: The economic cost of crime in SA”, The World Bank, 2023

Share

Did you enjoy this article?

South Africa

South Africa Namibia

Namibia

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter