SA monetary policy: Managing through an important juncture

In managing the M&G Enhanced Income Fund we pay particular attention to the interest rate cycle of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB). The path of the SARB repurchase rate (repo rate), as the base interest rate of the local economy, affects the pricing of all interest-bearing assets along the term structure, with short-dated instruments being more sensitive to changes in the repo rate and longer-dated ones being less so. It is in our clients’ best interest (and those of savers in general) that the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the SARB maintains positive real interest rates as well as a sufficient spread over global policy rates. This is to ensure that investors’ hard-earned savings are protected from local inflation dynamics, as well as to protect the value of their investments in foreign currency terms. It is also simply good policy for the country.

An important juncture

The MPC raised the repo rate by a cumulative 4.75% between November 2021 and May 2023, taking the policy rate from a record low of 3.50% to its current 8.25%. By all accounts, we are now at or near the tail-end of the hiking cycle. The committee is struggling to muster enough votes for further hikes, as evidenced by the 3-2 member votes in favour of unchanged policy rates at both the July and September MPC meetings. However, the MPC’s statements and subsequent Q&A sessions have still been hawkish. As is always the case, actions speak louder than words, and the MPC has now been relying on Open Mouth Operations (OMO) to guide inflation expectations lower. It is important to understand how monetary policy has evolved to get us to the current juncture.

Trying to maintain positive real interest rates

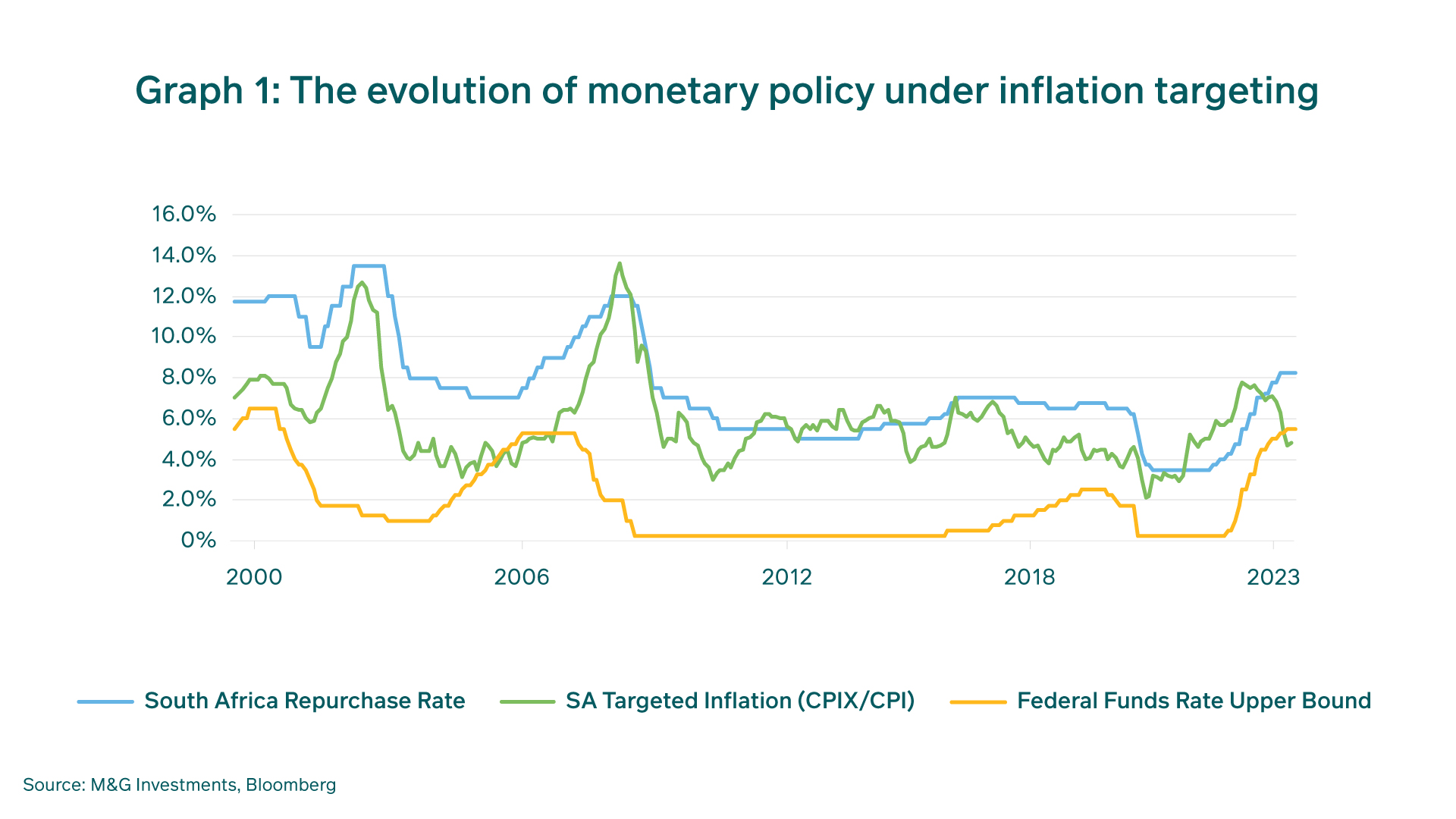

Since the introduction of the inflation targeting monetary policy framework at the turn of the century, the MPC has broadly maintained positive real interest rates to combat both inflation and higher inflation expectations. They initially dipped into a brief five-month period of negative real interest rates when they opted to look through the commodity price- fuelled peak in inflation during 2008 (Graph 1). However, in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the SARB experimented with negative real interest rates for over three years in order to support economic activity, which had dire consequences for inflation expectations and by implication its own credibility. In a speech by current SARB Governor Lesetja Kganyago entitled “South Africa’s growth performance and monetary policy” at the Bureau for Economic Research conference on 22 October 2015, he admitted to the folly of the experiment. He stated that: “For a flexible-inflation-targeting central bank facing persistently sub-par growth, there was a robust case against responding to these price developments. But that did not make the choice free. The policy had costs. And the benefits disappointed”.

To regain credibility, the MPC under Kganyago resolved to maintain positive real interest rates and aim to anchor inflation expectations at 4.5% (the midpoint of the 3%-6% inflation target range) instead of the 6% upper limit. This was a success, with both actual inflation and surveyed inflation expectations converging at 4.5% in the lead-up to the Covid pandemic. Then, in the face of the global growth shock and the oil price-induced trough in inflation during the height of the pandemic, the MPC cut interest rates aggressively to record low levels. Positive real interest rates were maintained until March 2021; however, once the base effects arising from low-to- negative oil prices entered the fray, inflation rebounded sharply. History shows that there is an asymmetry in the monetary policy decision-making process, whereby policymakers are prone to cut but reluctant to hike interest rates by looking-through peaks but acting on troughs in inflation.

Behind the curve

Even if one believes that the rapid 2.75% worth of interest rate cuts in the wake of the Covid outbreak were justified as emergency measures taken during the height of a pandemic, one must admit that once things normalised, they were no longer necessary. With the benefit of hindsight, which is always a perfect science, the hiking cycle should have started in January 2021, instead of 10 months later. We must remember that the MPC is composed of members who are every much as human as us. The human condition is such that we are reluctant to reverse course soon after making decisions, therefore explaining the lags between each phase of the interest rate cycle. To have hiked only six months after the last cut in July 2020 would have been prudent, but not an easy decision to make. Turning points in a cycle are, after all ,the most difficult period for central bankers to navigate.

By acting sooner, the MPC would have avoided the period of negative real interest rates that prevailed for over 18 months, from April 2021 to December 2022. This had the unwelcome effect of increasing inflation expectations, as indicated by breakeven-inflation rates implied by the bond market, as shown in Graph 2. These rates are the difference between the nominal yields on conventional bonds and the real yields on inflation-linked bonds. For those who did not understand the description “behind the curve” in late 2021, they were availed of the seriousness of the situation shortly thereafter when the MPC upped the ante with three consecutive 0.75% hikes from July 2022 to November 2022. Obviously, the global inflationary environment had accelerated in 2022 with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and its concomitant effect on key commodity prices and the initiation of the hiking cycle by the US Federal Reserve.

Where to next?

It is critical that the policy rate in South Africa not only takes the local inflation dynamic into account, but also global policy conditions. An appropriate risk premium for the many risk factors that abound domestically should be applied over and above the global policy rate. The rand is primarily traded against the US dollar, and while the SARB has hiked the repo rate by 4.75%, the Federal Reserve has hiked by 5.25%. This has led to a narrowing in the interest rate differential, making the currency less attractive from an interest carry perspective. It is no coincidence that the rand has been a notable underperformer in the emerging market (EM) currency universe year to date. An interesting dichotomy over this domestic hiking cycle was the terminal level of interest rates expected (the final rate at which the SARB would stop hiking) between local and foreign investors. For some time, local investors expected the terminal rate to be 6%, while foreign investors and the Forward Rate Agreement (FRA) market expected 8%. Suffice to say that the global dynamics have played a far greater role than local ones in dictating the interest rate path.

Some global central banks have now paused in their hiking cycles, and others have begun to cut, while still others (primarily in the large, developed economies) could implement one more hike. Chile began the global monetary easing cycle on 29 July, followed soon thereafter by Brazil. In fact, Latin American central banks have run very orthodox monetary policy over this cycle, having been some of the first to hike interest rates and also the first to cut interest rates. Other EM central banks in our time zone have been less orthodox in their conduct of monetary policy. Poland, for example, cut rates by more than expected on 6 September and the Polish currency weakened as a result, as the decision appeared to have been politically motivated. There are lessons to be learned from the conduct of other central banks, including what not to do with monetary policy.

In South Africa, inflation peaked in the middle of 2022, yet the MPC continued hiking as global monetary policy rates were still marching higher and real rates were still negative. We now have positive real interest rates, and we are fortunate that the SARB has been on the more orthodox side of the global spectrum. Yet the recent surge in the oil price and the hawkish rhetoric by developed world central bankers have seen our FRA market price out rate cuts in favour of additional hikes going forward. The SARB has also remained vigilant. Economic growth outcomes have fared considerably better than originally forecast by the SARB, despite the headwinds posed by load-shedding and high interest rates. The deteriorating fiscal situation presents a clear risk to the rand and by implication inflation. Both consumer and business confidence are very depressed, and it is highly unlikely that monetary policy can improve them. We have seen that periods of easy monetary policy have just not provided much of a boost to SA’s economic growth.

The burden placed on the SARB cannot be underestimated, but from an investment management viewpoint the best outcome would be for it to maintain its inflation fighting credentials. How it navigates the highly uncertain local and global environment going forward is important for us in managing the M&G Enhanced Income Fund, as it influences our asset allocation decisions between holding fixed, floating or inflation-linked instruments as well as the overall level of interest rate and currency risk in the portfolio.

In the current hiking cycle we have been successful in that management, with the fund having returned 9.9% over the past 12 months compared to 7.3% from its benchmark, the STeFI Composite Index, and 8.3% from the average of its ASISA category. It ranked sixth out of 115 funds for performance for the 12 months to 31 August 2023.

Share

Did you enjoy this article?

South Africa

South Africa Namibia

Namibia

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter