That which fools you

“We know what happens to people who stay in the middle of the road. They get run over!”

― Aneurin Bevan

If you’re reading this periodical you’re likely familiar with the book “Fooled by Randomness” (by Nassim Nicholas Taleb) published in 2001. It became something of folklore artifact among finance professionals who started using the title as a colloquialism when referring to lucky people. The book more formally describes how sometimes we are all beneficiaries of random events. It was the first time many of us began thinking about randomness as an object, as opposed to just a word to describe variation – the idea has been gnawing at me ever since.

One of the areas discussed in the book is “beating the market”, which the author argues is a field of endeavour prone to the trickery of randomness.

Let’s try to simplify the task of beating the market – at a portfolio level, beating the market averages entails some combination of:

- Owning more of the stocks that have beaten the market – the winners;

- Owning less (or fewer) of the stocks that have underperformed the market – the losers.

The idea is easily understood, but the task of successfully executing this strategy can be much more involved. At the risk of stating the obvious, not only does one not know which stocks will be winners (or losers), but the probability is hardly known with any certainty either. And that’s before you encounter some unforeseeable event that changes everything. How does one then proceed to construct a portfolio with a higher probability of winning than losing?

Raw odds

What are the chances of selecting a winner in a portfolio?

This question is open-ended and requires more context to be useful. To illustrate the point, let’s have a look at a more simplified probabilistic game where the odds of success are known ahead of time – roulette. Keeping it simple, let’s assume we play the double-or-nothing bet – red or black. The odds of winning on any spin of the wheel is around 48% (47.4% for the American wheel with a double zero and 48.6% for the European variation of the game), so pretty close to even against the house. These odds are not drastically out of favour, but that changes quickly depending on the number of spins of the wheel a player is willing to wager on.

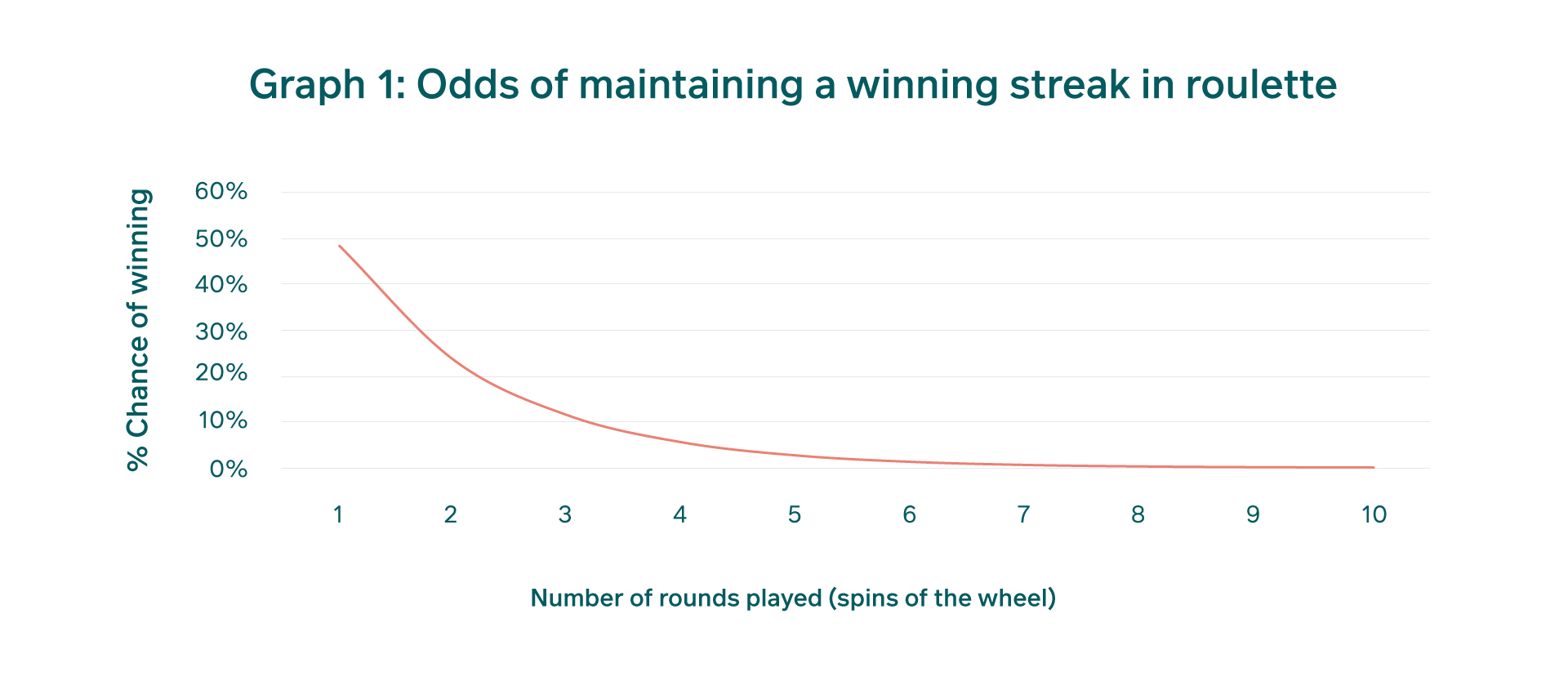

The best odds (48% chance of winning) are achieved on the very first spin of the wheel when a player has placed a wager. The odds of success then drop precipitously as a player continues to wager, such that by the fourth successive spin of the wheel the odds of maintaining a winning streak drop to only 5%. By the sixth spin, they’re barely 1%

Graph 1 illustrates the “raw odds” of winning at a game like roulette. This does not account for any strategic or tactical approach (not that it would matter in a game of chance, but worth mentioning).

Turning now to the raw odds of blindly selecting a winning stock, there are a few nuances to consider, with time frame being the most pertinent.

On any given day, the odds of holding a stock that will beat the market range from 20% to 55%. This is a wide range since there are an untold number of forces acting on the price of a stock in the short term. As we lengthen the time horizon though, observations become steadier and more intuitive. We’ve crunched some numbers for the FTSE/JSE All Share Index over the last decade based on publicly available data. The table below summarises the total share returns inclusive of dividends and share price performance (TSR) for ALSI constituents for which we had a complete dataset (after removing listings/de-listings, etc).

The results were unsurprising and the general trend was intuitive; we noted two key observations:

- Outperformers reduce as the holding period lengthens;

- Returns are more dispersed as the time horizon increases;

Randomness ahead, ignore at your peril

Roulette is not a game where the player can entrench an edge (without resorting to some rather unconventional methods as detailed in Ed Thorpe’s biography). So how does the casino (the house) do it and build a business around it?

The answer lies partly in the way they structure the game (the house has the edge) and partly in how each participant is permitted to play (the house can extract the edge at the players’ expense). The house draws its edge from the fact that there is no way of predicting the outcome of any spin of the wheel, using the information available. You have likely heard the probability cliché that even though a coin might have landed heads up five times in a row, the chance of the next toss remains 50/50. The same applies to each spin of a roulette wheel, so any individual player cannot gain an advantage.

The casino exploits its edge of around 1.5-2.5% by playing against multiple players, spread over many tables across numerous locations. With so many thousands of spins of the wheel and the casino’s inherent, albeit marginal, edge, a steady stream of rather predictable profitability can be extracted, in aggregate. To win at these sorts of games, both an edge and the ability to exploit the edge is required – that is what the house has that the individual player does not.

Most day traders lose money because the nature of the game they’re playing is closer to roulette. It is notoriously challenging to establish an edge in day trading because there are so many variables weighing on the short-term price movements of a stock. And then, even if an edge has been established, it needs to be large enough and occur with sufficient regularity such that exploiting it for profit is feasible. Unlike a casino where the edge is ever-present, the challenge most day traders face is that they do not know exactly when their edge will show up. They must keep trying their luck until a winning streak lands. The cost of trial and error is often insurmountable, and most die a death of a thousand cuts or lose patience and blow-up by over-betting.

Edge toward non-random

“…Just by lengthening the time horizon, you can engage in endeavours that you could never otherwise pursue” – Jeff Bezos

We’ve come a long way from our initial conceptual understanding of what is required to beat the market averages, and I’d like to re-iterate that beating the market requires owning more of the winners while also avoiding more of the losers. Furthermore, we saw in the analysis above that as we extend the time horizon, the percentage of winners dwindles, thus making the task more challenging.

A natural enquiry at this point is to ask whether persistence is apparent among winning stocks such that we may escape the clutches of randomness when it comes to stock selection. The answer is not straight forward and depends on how one looks at it. Persistence is apparent in shareholder returns through time not because the winning stocks of yesterday are the winning stocks of tomorrow, but because winning streaks in the winning stocks carry those winners for a long time. Graph 3 tracks the TSR of the top 40 best-performing ALSI stocks over the decade ending December 2021. Included in the figure is a measure of persistence (# of common stocks; % of common stocks). This tracks the number (and percentage of the 40 stocks) that are common to the period in question and the 10- year period. For example, of the 40 top-returning stocks over the 10-year time period, 27 of them were among the top 40 best-performing stocks over five years. There are two noteworthy observations:

- Over shorter time horizons (1-3 years), persistence scores seem closer to random, and it is only over the medium term that a degree of persistence can be perceived.

- Winning streaks tend to carry the best performers as long-term winners even though there may be periods of extended underperformance. Some of the long-term winners that have underperformed in the shorter term include Mondi, Coronation and Discovery.

Removing elements of randomness is how one develops an edge in probabilistic games. By removing the noise of random occurrences, much of which serve to cancel each other out over longer time horizons, we can focus on those elements that lead to outperformance. Many of these elements revolve around a company’s ability to earn excess returns over a prolonged period of time and reinvest at rates that maintain those high returns. Now there are many sub-elements that contribute to excess returns, including the sector within which the company operates, level of redundancy that products are subject to and the quality of the management team, amongst others.

To get the odds on our side over the long term at M&G, our process is structured to ensure we are focussed on these long run anchors supporting value.

Staying lucid in the face of the siren song of randomness is tricky at the best of times, but the line between being fooled and being killed is thin indeed.

Share

Did you enjoy this article?

South Africa

South Africa Namibia

Namibia

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter